A woman’s right to enjoy the city

As part of our series on eliminating violence against women and girls in our cities produced in collaboration with the Huairou Commission, Mumbai architect Pallavi Shrivastava offers a personal reflection on how the threat of violence forces women not only to change our movements but also prevents us from enjoying our cities, and thus from helping to make them the cities we want them to be.

Home to 5.5 million women, Mumbai is considered one of the most modern, cosmopolitan and safe cities for women in India. Yet, not a day goes by without news of a woman of any age or class being molested, attacked, sexually harassed, compromised or violated in some way. With recent debate spurred by the incident in Delhi of a 23-year-old girl being mob-raped in a moving bus and then beaten and left to die, it is important to question the forces that lead to this reprehensible behaviour against women and how much of it is facilitated by planned and unplanned urban spaces.

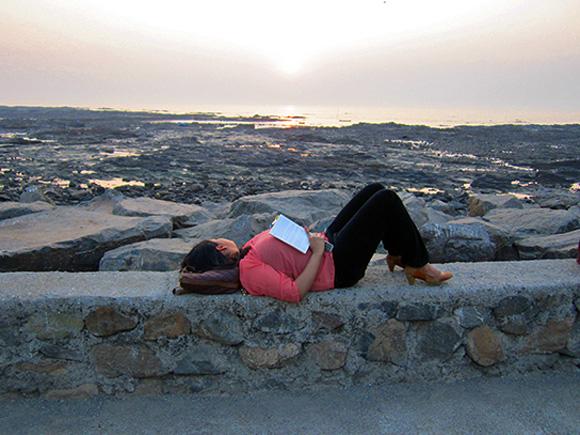

A woman watches the sunset while reclining on a sea wall in Mumbai, enjoying a freedom of the city that many of her female compatriots in Delhi, Mumbai and many other cities cannot take for granted. Photo: Pallavi Shrivastava

The phenomenon of women keeping away from public spaces because of physical threat is common in India. Growing up in Mumbai, I had internalised this as second nature, allowing it to determine what my movement through the city would be. Stay indoors after dark; move in herds of friends or male company, or at least in the company of a known person; always be on guard in public, especially on public transport; and later, keep questioning whether the groping, letching, staring, or whistling was accidental or intentional. This kind of covered, negotiated presence in public space is true for most Indian women. Each has devised their own compromised mode of urban movement whether it’s to the office, college or merely going out.

What does this do to women’s role in the society? It compels them to revise, revisit, modify and adjust their plans of being. They negotiate where and when they can go on an everyday basis. They question the appropriateness of their clothing choices and seek revalidation on their movement. This is a limitation of movement and behaviour that has much larger implications for women’s role in society. This is strikingly different to what access to public spaces provides to men. As they grow into adults, they expand and move in urban spaces freely, thus giving them access to almost any space, any time of the day. This enables men to have more freedom in seeking suitable employment, easier access to education and more possibilities for moving upwards socially.

This imbalance, this lop-sided access to choices has women feeling they are less human. The very idea that women can be out in open urban spaces on their own is not a given in a society where paternalism is so often implicit in even the most well-meaning advice. It is unsurprising that we do not see many women in leadership roles here. With such a deeply ingrained habit of treating women as dependent, and therefore secondary citizens, how does India intend to provide equal access to urban spaces outside their homes?

THE RIGHT TO ENJOY THE CITY

This lack of access not just denies women their rights; it also curbs their participation in shaping the future city in which they desire to live, where citizens of all genders can all go out and claim the city with their actual physical self by walking, running, jogging, encountering, strolling, lying on the beach, and soaking up the sun.

We need to make the city unequivocally a place of belonging, exploration and enjoyment. Functional infrastructure in the form of safe public transport, toilets, well-lit streets, and safe urban spaces remains at the core of the issue. But access to public spaces like promenades, beaches, sidewalks, parks, libraries, and running tracks are already required of a well-designed and inclusive city irrespective of gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity or economic class. We must also attempt to change cultural patterns and legal systems, educating police and local authorities to be more responsive to women’s concerns, to change this subversive culture of casting women as secondary citizens. Whereas what we are witnessing in India today are efforts to seclude ourselves from these urban issues by creating sanitised ‘bubble’ developments which boast of superficialities.

It is our public spaces that communicate a city’s attitude towards its citizens. The presence of well-designed infrastructure and inviting places are a measure of its inclusiveness. Can we design urban spaces that are sensitive to everybody? We have to begin now and make conscious efforts to make India’s cities inclusive, just and inviting. I truly believe that India is on the brink of dramatic change. How that change can be fostered will be up to the citizens of the country.

Pallavi Shrivastava is an architect working in Mumbai.

Source: Link