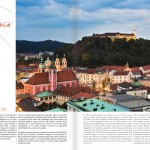

Ljubljana; An Ideal City

Selçuk Avcı argues that Ljubljana might be an ideal city at the last issue of the Konsept Projeler Magazine.

” In 1991 Slovenia entered into a short war out of which it came relatively unhurt. After a ten-day war during which my wife and I were in London, only able to helplessly watch, Ljubljana emerged a capital city of a newly independent small state of 2 million people. It was handed over to people hungry to have something that they can wholly call their own. And she, with its people came out of a long slumber triggered by the stultifying imposition of a totalitarian moderately communist state, which remained in existence some 46 years after its formation in 1945. But ironically through this experience Slovenia earned the chance to become a sovereign state for the first time in its history and with this new beginning Ljubljana blossomed as one of the most beautiful cities in Europe, so much so that its old inhabitants, and its most recent ones like me, always find a reason to return home to this town.

By the end of 1991, handed over their freedom, the inhabitants took over a city left in neglect, uncared for and devoid of energy much like many beautiful cities laid to waste during the cold-war era. As never before in their long history the Slovenes had to find their own source of energy and live with the consequences of their decision to go it alone. Despite endemic macro-economic issues, which have only come to head now as Europe struggles in crisis, the city was successful in transforming itself in to one of the most livable cities in Europe and for this alone the Slovenes should be proud.

Although the origins of settlement go back far beyond this the Romans making a garrison town along the banks of the river Ljubljanica first started a city. The quadrangle of the Roman city Emona with its four gates and main axis such as the Slovenska Street, are now fully integrated into the fabric of the main center district of Ljubljana. However the city that we see today is the result of two distinct periods of development. The first is the medieval city following tightly the banks of the river, and rising at its peak to the castle of Ljubljana. The Slavs first settled below the castle hill in the 6th Century, and the city flourished until the end of the 19th Century under the rule of various foreign rulers, among who the Hubsburgs were most. This so-called “old city” is organic in its geometries; typical in that sense of a medieval pattern that snuggly fits the curving forms of the landscape. The second is the city that follows more the rectilinear forms on the south east, left by the Romans, creating axes and quadrangles within which lie public squares and streets of the Austro-Hungarian period; typical in that sense of what we see in many cities in this region. However the scale of this later 17-18th century development is still somewhat respectful of the medieval counterpart, playing its role of ordering the chaos of the old city with a sense of civility and repose.

Ljubljana was badly destroyed in the 19th Century by a great earthquake after which Max Fabiani, a Viennese architect of Slovene descent drew up a master plan, which became the backbone of its modern development in to the 20th Century. 30 Years after Fabiani, Jože Plečnik was asked to develop an urban plan as the city architect. It is in this era that much of the edges of the Ljubljanica and many public spaces and public buildings were given a unique identity. Today the spirit he breathed into the city is kept alive in public projects along the edges of the river and many squares by the new Municipal Administration and its Deputy Mayor who happens to be an architect Janez Koželj, who is also a professor at the school of architecture at the University of Ljubljana, has made great progress from the very beginning of his tenure.

This lies at the heart of what makes a city progressively a better place. The clear and singular attention of at least one man, a city architect, who cares for the future of the city with singular devotion and works to achieve that come what may. Of course he does not do that alone. The process involves a kind of orchestration, much like a conductor who composes the overall score and guides the beautiful instruments, which come together to make a wonderful sound.

Ljubljana adheres as closely as possible to the competition system when it comes to giving commissions to architects, such as the market bridge Mesarski most, by Jurij Kobe, or the new national library project NUK2 by Bevk Perović which is yet to be built.

Going back to Jože Plečnik though, much of what we see and appreciate about the centre of Ljubljana and how it works is the result of his work. The Three Bridges across the river at the center of town connecting Presern Square with Mestni trg are an unusual gem, which now that the traffic has been removed from the center of town lives as a public space over the river. It is this tradition of the market bridge connecting the market square with the opposite shore of the river that is continued by Jurij Kobe. And somehow Plečnik’s quirky ideas live on in the modern architecture of Ljubljana. Even Kozelj was at the beginning of his career was inspired directly by Plečnik’s Flat Iron Building in Prešern when designing the residential project in Poljanska. This particularity of the city of Ljubljana comes from a love affair with the city, that at that time one man pursued with fervor and personal zest. Any city, if it is to flourish, needs that kind of love. This process is still continued today by the Deputy Mayor of Ljubljana. And as long as it is Ljubljana will become more and more an ideal city.

A big and important move to make by the municipality was the decision to gradually bring under control the intrusion into the center by cars, and the further encouragement of walking and cycling to this end. This departure of the car from the immediate vicinity of public spaces and routes, or its diminishing role within the city is what makes Ljubljana a particularly livable city. The disappearance of the car makes the city more and more hospitable, as inhabitants treat the streets and public squares as extensions of their living rooms. Indeed the river side of the center of Ljubljana often behaves as if it is one long room, much like many public piazzas in Italian towns, where the ‘corso’ or the promenade is practiced by the inhabitants to interact with each other in a domain which is totally shared.

What is interesting about Ljubljana is this sense of ownership by its residents that is amplified through the work of the municipality. Visitors must feel this ownership as they enter in to the city, a kind of private / public sanctum. Almost an intrusion but nevertheless a welcome one. This is not dissimilar to the village centers of London, such as Primrose Hill or Islington, or Hampstead where when we enter those centres we feel as if we are entering into a different place. Ljubljana is in that sense a microcosm in itself. For this to function the size of the living unit or the micro-city has to be small enough to induce a sense of ownership. And for this ownership to take shape, the city needs essential parts that make a whole, much like the way our body makes a whole with the combination of its parts, all of it essential for the functioning of the body.

Therefore size is important in introducing the idea of an ideal community. But the greater community, made up of these smaller units can grow to pretty much any size as long as it has within it the right components. In that sense Ljubljana has all of these attributes of an ideal enclave. A scale of parts that are humane in their relationship to the body, coherently formed of organs for breathing such as great parks and tree lined squares and streets, or structural elements that pull it together such as a good movement system that does not rely entirely on the car, as well as a hierarchy of elements that come together to appropriately make an administrative whole. All of this of course comes together in Ljubljana over a period of history, fortuitously because of this love and care with which it has been developed.

Having just visited Paris I am reminded that this is not so different in a larger city as well. It is just that the parts are much bigger. Bigger boulevards, bigger parks, bigger moves in terms of connections, but what is consistent is the singular attention of a city architect: Haussmann. Ljubljana had it’s own starting with Fabiani, then Plečnik, now Koželj. The lesson we learn from this is clear: Cities like all of us need love, and care and attention, and they need this from a consistent source that gives it coherence and oneness, a wholesomeness that is palpable.”